A Storied Legacy of Honor and Sacrifice

_

At the request of the

Continental Congress, the Provincial Congress of South Carolina met in June of 1775 to

raise two regiments of infantry. William Moultrie, a veteran officer from the French and Indian War, was appointed Colonel commanding the 2nd Regiment. Junior officers were quickly appointed, among them Capt. Francis Marion. Within days, the officers were sent into the countryside to begin recruiting.

On September 13, in the first act of the armed rebellion in South Carolina, several companies of the 1st and 2nd Regiments were ordered to capture Ft. Johnson, located on James Island to the south of the Charleston Harbor entrance. Landing ashore from boats, they rushed the fort, only to find the doors open, with a small British guard waiting to surrender the fort.

In February 1776, Governor Edward Rutledge ordered a fort to be built on the southern end of Sullivan's Island, guarding the northern approaches to Charleston Harbor. The work progressed steadily, but the palmetto-log structure was still incomplete by the summer, when a large British invasion fleet appeared of the coast.

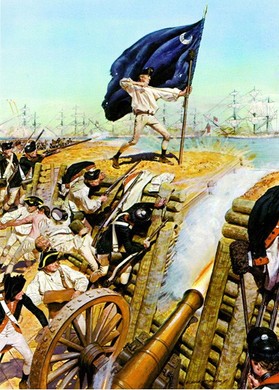

On July 28, 1776, after several weeks of skirmishing and feints, the British, under Gen. Sir Henry Clinton and Adm. Sir Peter Parker, launched a combined naval and land attack on Sullivan's Island. While Clinton's men attempted an unsuccessful amphibious assault on the northern end of the island, Parker's fleet of ten armed vessels bombarded the palmetto-log fort, garrisoned by the 2nd Regiment, with assistance from the 4th Regiment of Artillery. The 250 guns of the British fleet opened fire around 10 AM; the 2nd Regiment answered with a slow but deliberate and deadly accurate fire, largely directed by now-Major Francis Marion. An eyewitness wrote, "A most tremendous cannonade ensued...Col. Moultrie, with 344 regulars and a few volunteer militia, made a defense that would have done honor to experienced veterans." During the attack, the American flagstaff was shot away. Sergeant William Jasper tied the Americans' flag (deep blue with a crescent and the word "LIBERTY" in white) to a sponge staff and planted it defiantly upon the parapet of the fort. With firing being almost continuous until early evening, the battle finally ended around 9 PM. The British suffered severe losses: one ship sunk, all ships suffering major damage, and 200 men killed or wounded. In contrast, the palmetto-log fort had been largely unharmed, and American losses were placed at around 35 killed or wounded. This action was one of the greatest defeats for the British Navy in its history.

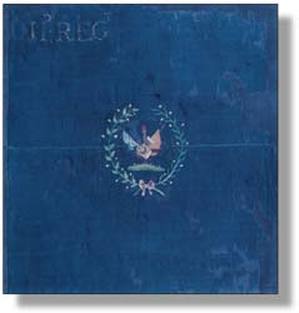

The 2nd Regiment was immediately recognized for its gallant action. On July 1, 1776, The regiment was presented a pair of silk colors by Mrs. Bernard Elliott. The Colors were "an elegant pair of colors... one of a fine blue silk, the other of a fine red silk, richly embroidered." In presenting the colors, Mrs. Elliot declared, "Your gallant behavior in Defense of Liberty & your Country Entitles you to the Highest Honours . . ."

The 2nd Regiment spent most of the next three years in garrison duty in and around Charleston, occasionally venturing into the field to meet British threats in the Lowcountry between Charleston and Savannah. During this time, William Moultrie was promoted to Brigadier General; by 1778, Francis Marion had risen to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel, and was appointed commander of the regiment.

On October 9, 1779, the blue colors were lost in the Battle of Spring Hill Redoubt during the French and American Siege of Savannah. Four color bearers were lost in the action. A Captain in the Royal American Regiment wrote "at the assault on Spring Hill redoubt, Lieutenant Bush being wounded handed the blue color to Sergeant Jasper. Jasper, who had already received a bullet, was then mortally wounded, but returned the color to Bush who the next minute fell, yet even in the moment of death attempted to protect the flag which was afterwards found beneath him. No one could have done more, and the color hallowed by the blood of Bush and Jasper, deserves to be deposited under a consecrated roof". Jasper managed to carry the red color off the field, but died the next day of his wounds. The blue color was for many years at the museum of the 60th Regiment, The Kings Royal Rifle Corps, at Winchester, England. It has since been returned to this country and is on alternating display at the Smithsonian Institute and the South Carolina State Museum.

The regiment continued to serve until it was surrendered with the Southern Army at the fall of Charleston in May, 1780. The regiment’s traditions of resourcefulness and bravery continued on in the exploits of Francis Marion, the former commandant of the 2nd Regiment who continued fighting as the “The Swamp Fox” in legendary guerrilla campaigns until the British were finally driven out of South Carolina in 1782.

On September 13, in the first act of the armed rebellion in South Carolina, several companies of the 1st and 2nd Regiments were ordered to capture Ft. Johnson, located on James Island to the south of the Charleston Harbor entrance. Landing ashore from boats, they rushed the fort, only to find the doors open, with a small British guard waiting to surrender the fort.

In February 1776, Governor Edward Rutledge ordered a fort to be built on the southern end of Sullivan's Island, guarding the northern approaches to Charleston Harbor. The work progressed steadily, but the palmetto-log structure was still incomplete by the summer, when a large British invasion fleet appeared of the coast.

On July 28, 1776, after several weeks of skirmishing and feints, the British, under Gen. Sir Henry Clinton and Adm. Sir Peter Parker, launched a combined naval and land attack on Sullivan's Island. While Clinton's men attempted an unsuccessful amphibious assault on the northern end of the island, Parker's fleet of ten armed vessels bombarded the palmetto-log fort, garrisoned by the 2nd Regiment, with assistance from the 4th Regiment of Artillery. The 250 guns of the British fleet opened fire around 10 AM; the 2nd Regiment answered with a slow but deliberate and deadly accurate fire, largely directed by now-Major Francis Marion. An eyewitness wrote, "A most tremendous cannonade ensued...Col. Moultrie, with 344 regulars and a few volunteer militia, made a defense that would have done honor to experienced veterans." During the attack, the American flagstaff was shot away. Sergeant William Jasper tied the Americans' flag (deep blue with a crescent and the word "LIBERTY" in white) to a sponge staff and planted it defiantly upon the parapet of the fort. With firing being almost continuous until early evening, the battle finally ended around 9 PM. The British suffered severe losses: one ship sunk, all ships suffering major damage, and 200 men killed or wounded. In contrast, the palmetto-log fort had been largely unharmed, and American losses were placed at around 35 killed or wounded. This action was one of the greatest defeats for the British Navy in its history.

The 2nd Regiment was immediately recognized for its gallant action. On July 1, 1776, The regiment was presented a pair of silk colors by Mrs. Bernard Elliott. The Colors were "an elegant pair of colors... one of a fine blue silk, the other of a fine red silk, richly embroidered." In presenting the colors, Mrs. Elliot declared, "Your gallant behavior in Defense of Liberty & your Country Entitles you to the Highest Honours . . ."

The 2nd Regiment spent most of the next three years in garrison duty in and around Charleston, occasionally venturing into the field to meet British threats in the Lowcountry between Charleston and Savannah. During this time, William Moultrie was promoted to Brigadier General; by 1778, Francis Marion had risen to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel, and was appointed commander of the regiment.

On October 9, 1779, the blue colors were lost in the Battle of Spring Hill Redoubt during the French and American Siege of Savannah. Four color bearers were lost in the action. A Captain in the Royal American Regiment wrote "at the assault on Spring Hill redoubt, Lieutenant Bush being wounded handed the blue color to Sergeant Jasper. Jasper, who had already received a bullet, was then mortally wounded, but returned the color to Bush who the next minute fell, yet even in the moment of death attempted to protect the flag which was afterwards found beneath him. No one could have done more, and the color hallowed by the blood of Bush and Jasper, deserves to be deposited under a consecrated roof". Jasper managed to carry the red color off the field, but died the next day of his wounds. The blue color was for many years at the museum of the 60th Regiment, The Kings Royal Rifle Corps, at Winchester, England. It has since been returned to this country and is on alternating display at the Smithsonian Institute and the South Carolina State Museum.

The regiment continued to serve until it was surrendered with the Southern Army at the fall of Charleston in May, 1780. The regiment’s traditions of resourcefulness and bravery continued on in the exploits of Francis Marion, the former commandant of the 2nd Regiment who continued fighting as the “The Swamp Fox” in legendary guerrilla campaigns until the British were finally driven out of South Carolina in 1782.

The Heroes: Moultrie, Marion and Jasper

While all of the men who served with the 2nd Regiment were true heroes, the fame and exploits of three men have carried into modern times: Moultrie, Marion and Jasper.

William Moultrie, esteemed for his cool command of the regiment at the Battle of Sullivan's Island, rose to the rank of Major General in the Continental Army and was later Governor of South Carolina. His memoirs are an invaluable account of the war in the Southern theater.

Francis Marion, the last commander of the regiment, won later fame as the legendary "Swamp Fox", almost single-handedly keeping the war alive in the south for a period of time by leading a small band of militia and ex-soldiers in a guerilla-style campaign against the British in the South Carolina Lowcountry. His tactics have been studied by military leaders around the world.

William Jasper was offered a battlefield commission for his daring act of planting the flag on the parapet of the palmetto-log fort at Sullivan's Island while under fire on June 28, 1776; he turned it down, preferring to remain in the ranks as a non-commissioned officer. His bravery in saving the Regiment's red color while mortally wounded at Savannah is commemorated today by a statue of him in that city. Jasper remains THE most famous American non-commissioned officer of the Revolutionary War.

All told, these three men have had innumerable honors bestowed upon them. Numerous cities, counties, lakes, parks, forests and schools around the nation have been named after them; multiple statues of them have been erected as well. To this day, all school children in South Carolina know the names Moultrie, Marion and Jasper.

William Moultrie, esteemed for his cool command of the regiment at the Battle of Sullivan's Island, rose to the rank of Major General in the Continental Army and was later Governor of South Carolina. His memoirs are an invaluable account of the war in the Southern theater.

Francis Marion, the last commander of the regiment, won later fame as the legendary "Swamp Fox", almost single-handedly keeping the war alive in the south for a period of time by leading a small band of militia and ex-soldiers in a guerilla-style campaign against the British in the South Carolina Lowcountry. His tactics have been studied by military leaders around the world.

William Jasper was offered a battlefield commission for his daring act of planting the flag on the parapet of the palmetto-log fort at Sullivan's Island while under fire on June 28, 1776; he turned it down, preferring to remain in the ranks as a non-commissioned officer. His bravery in saving the Regiment's red color while mortally wounded at Savannah is commemorated today by a statue of him in that city. Jasper remains THE most famous American non-commissioned officer of the Revolutionary War.

All told, these three men have had innumerable honors bestowed upon them. Numerous cities, counties, lakes, parks, forests and schools around the nation have been named after them; multiple statues of them have been erected as well. To this day, all school children in South Carolina know the names Moultrie, Marion and Jasper.

The South Carolina State Flag

The modern flag of South Carolina is a tribute to the 2nd Regiment. The blue field with a crescent (now incorrectly angled) comes from the flag used at the Battle of Sullivan's Island. The deep blue color came from the coats worn by the regiment, and an (upright) crescent was a symbol of South Carolina military organizations dating back to the French and Indian War.

Variations of this flag were used by the state until the Civil War, when state leaders added a palmetto tree to the flag, partly in honor of the Battle of Sullivan's Island, and partly due to the recognition of the South Carolina's nickname as the "Palmetto State." The modern flag was officially adopted on June 28, 1861, the 85th anniversary of the Battle of Sullivan's Island.

Variations of this flag were used by the state until the Civil War, when state leaders added a palmetto tree to the flag, partly in honor of the Battle of Sullivan's Island, and partly due to the recognition of the South Carolina's nickname as the "Palmetto State." The modern flag was officially adopted on June 28, 1861, the 85th anniversary of the Battle of Sullivan's Island.